At my favorite professor's dinner party,

years ago, I gave birth

to what I thought was a new idea,

and the room got quiet

with tolerance. I still hear that tolerance.

-

Spring Feature 2013

-

Feature

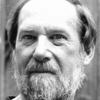

- Billy Collins Billy Collins in conversation with Ginger Murchison

- AWP 2013 Greetings Video greetings from the AWP 2013 Bookfair

-

Poetry

-

Review

- David Rigsbeeon this year's AWP Conference

Feature > Poetry

If a Clown

If a clown came out of the woods,

a standard looking clown with oversized

polkadot clothes, floppy shoes,

a red, bulbous nose, and you saw him

on the edge of your property,

there'd be nothing funny about that,

would there? A bear might be preferable,

especially if black and berry-driven.

And if this clown began waving his hands

with those big, white gloves

that clowns wear, and you realized

he wanted your attention, had something

apparently urgent to tell you,

would you pivot and run from him,

or stay put, as my friend did, who seemed

to understand here was a clown

who didn't know where he was,

a clown without a context.

What could be sadder, my friend thought,

than a clown in need of a context?

If then the clown said to you

that he was on his way to a kid's

birthday party, his car had broken down,

and he needed a ride, would you give

him one? Or would the connection

between the comic and the appalling,

as it pertained to clowns, be suddenly so clear

that you'd be paralyzed by it?

And if you were the clown, and my friend

hesitated, as he did, would you make

a sad face, and with an enormous finger

wipe away an imaginary tear? How far

would you trust your art? I can tell you

it worked. Most of the guests had gone

when my friend and the clown drove up,

and the family was angry. But the clown

twisted a balloon into the shape of a bird

and gave it to the kid, who smiled,

letting it rise to the ceiling. If you were the kid,

the birthday boy, what from then on

would be your relationship with disappointment?

With joy? Whom would you blame or extol?

a standard looking clown with oversized

polkadot clothes, floppy shoes,

a red, bulbous nose, and you saw him

on the edge of your property,

there'd be nothing funny about that,

would there? A bear might be preferable,

especially if black and berry-driven.

And if this clown began waving his hands

with those big, white gloves

that clowns wear, and you realized

he wanted your attention, had something

apparently urgent to tell you,

would you pivot and run from him,

or stay put, as my friend did, who seemed

to understand here was a clown

who didn't know where he was,

a clown without a context.

What could be sadder, my friend thought,

than a clown in need of a context?

If then the clown said to you

that he was on his way to a kid's

birthday party, his car had broken down,

and he needed a ride, would you give

him one? Or would the connection

between the comic and the appalling,

as it pertained to clowns, be suddenly so clear

that you'd be paralyzed by it?

And if you were the clown, and my friend

hesitated, as he did, would you make

a sad face, and with an enormous finger

wipe away an imaginary tear? How far

would you trust your art? I can tell you

it worked. Most of the guests had gone

when my friend and the clown drove up,

and the family was angry. But the clown

twisted a balloon into the shape of a bird

and gave it to the kid, who smiled,

letting it rise to the ceiling. If you were the kid,

the birthday boy, what from then on

would be your relationship with disappointment?

With joy? Whom would you blame or extol?

Love

Found dead in an alley

of words: awesome,

no hope for it, and share,

which must have fallen

trying to get by on its own,

and near the trash cans,

almost totally exhausted,

the barely breathing cool.

But there's love

among the disposables,

waiting, as ever,

to be lifted

into consequence.

And here comes a forager

looking for anything

that might get him

through another night.

Love's right in front

of him, his if he wants it.

In the air

the ashy smell of cliches,

the stink of obsolescence.

He's leaning love's way.

All the words are watching,

even the dead ones. It's as if

what he does next

could be the equivalent

of restoring awe to awesome —

that love, if chosen,

might be given back to love,

made new again.

But the man is just a man

out for easy pickings.

Or has he just remembered

how, early on, love

always feels original?

Let us forgive him

if he keeps on foraging.

of words: awesome,

no hope for it, and share,

which must have fallen

trying to get by on its own,

and near the trash cans,

almost totally exhausted,

the barely breathing cool.

But there's love

among the disposables,

waiting, as ever,

to be lifted

into consequence.

And here comes a forager

looking for anything

that might get him

through another night.

Love's right in front

of him, his if he wants it.

In the air

the ashy smell of cliches,

the stink of obsolescence.

He's leaning love's way.

All the words are watching,

even the dead ones. It's as if

what he does next

could be the equivalent

of restoring awe to awesome —

that love, if chosen,

might be given back to love,

made new again.

But the man is just a man

out for easy pickings.

Or has he just remembered

how, early on, love

always feels original?

Let us forgive him

if he keeps on foraging.

Talk to God

Thank him for your little house

on the periphery, its splendid view

of the wildflowers in summer,

and the nervous, forked prints of deer

in that same field after a snowstorm.

Thank him even for the monotony

that drives us to make and destroy

and dissect what would otherwise be

merely the lush, unnamed world.

Ease into your misgivings.

Ask him if in his weakness

he was ever responsible

for a pettiness — some weather, say,

brought in to show who's boss

when no one seemed sufficiently moved

by a sunset, or the shape of an egg.

Ask him if when he gave us desire

he had underestimated its power.

And when, if ever, did he realize

love is not inspired by obedience?

Be respectful when you confess to him

you began to redefine heaven

as you discovered certain pleasures.

And sympathize with how sad it is

that awe has been replaced

by small enthusiasms, that you're aware

things just aren't the same these days,

that you wish for him a few evenings

surrounded by the old, stunned silence.

Maybe it will be possible then

to ask, Why this sorry state of affairs?

Why — after so much hatefulness

done in his name - no list of corrections

nailed to some rectory door?

Remember to thank him for the silkworm,

apples in season, photosynthesis,

the northern lights. And be sincere.

But let it be known you're willing to suffer

only in proportion to your errors,

not one unfair moment more.

Insist on this as if it could be granted:

Not one moment more.

on the periphery, its splendid view

of the wildflowers in summer,

and the nervous, forked prints of deer

in that same field after a snowstorm.

Thank him even for the monotony

that drives us to make and destroy

and dissect what would otherwise be

merely the lush, unnamed world.

Ease into your misgivings.

Ask him if in his weakness

he was ever responsible

for a pettiness — some weather, say,

brought in to show who's boss

when no one seemed sufficiently moved

by a sunset, or the shape of an egg.

Ask him if when he gave us desire

he had underestimated its power.

And when, if ever, did he realize

love is not inspired by obedience?

Be respectful when you confess to him

you began to redefine heaven

as you discovered certain pleasures.

And sympathize with how sad it is

that awe has been replaced

by small enthusiasms, that you're aware

things just aren't the same these days,

that you wish for him a few evenings

surrounded by the old, stunned silence.

Maybe it will be possible then

to ask, Why this sorry state of affairs?

Why — after so much hatefulness

done in his name - no list of corrections

nailed to some rectory door?

Remember to thank him for the silkworm,

apples in season, photosynthesis,

the northern lights. And be sincere.

But let it be known you're willing to suffer

only in proportion to your errors,

not one unfair moment more.

Insist on this as if it could be granted:

Not one moment more.

Intrusions

The narcissists, as ever, were rhyming themselves

with themselves, while a few houses away,

a man with a certain urgency, but with no

philosophical position on the matter,

wanted early morning sex

more than did his wife. She wasn't a prude.

She just liked to be wooed

before being pinned down, wanted her eyes

more than half open, didn't want

to feel like some opening act.

It was clear an ape lived somewhere

in the man's past, and could — at the right time —

be seen in the woman's behavior, too,

though the DNA of those small, fuck-crazy-

anytime-any-which-way bonobos monkeys

had been civilized out of her, or so it seemed.

Otherwise, she had efficient opposable thumbs,

and a desire to please him when she wasn't awakened

by a pressing issue not hers. One day the narcissists

dropped by uninvited just after dinner to offer

the importance of their presence. The man and woman

had been talking, taking turns, as it were, about why

she preferred something else to the Anglo-Saxon words

he used as a way of further arousing her into wakefulness.

They allowed their visitors to overhear the act

of thinking inside and outside a subject, because, after all,

the subject was intrusion, its niceties and violations,

and their neighbors were part of it now,

who had come wishing to communicate —that big word

certain people use who have no gift for it.

with themselves, while a few houses away,

a man with a certain urgency, but with no

philosophical position on the matter,

wanted early morning sex

more than did his wife. She wasn't a prude.

She just liked to be wooed

before being pinned down, wanted her eyes

more than half open, didn't want

to feel like some opening act.

It was clear an ape lived somewhere

in the man's past, and could — at the right time —

be seen in the woman's behavior, too,

though the DNA of those small, fuck-crazy-

anytime-any-which-way bonobos monkeys

had been civilized out of her, or so it seemed.

Otherwise, she had efficient opposable thumbs,

and a desire to please him when she wasn't awakened

by a pressing issue not hers. One day the narcissists

dropped by uninvited just after dinner to offer

the importance of their presence. The man and woman

had been talking, taking turns, as it were, about why

she preferred something else to the Anglo-Saxon words

he used as a way of further arousing her into wakefulness.

They allowed their visitors to overhear the act

of thinking inside and outside a subject, because, after all,

the subject was intrusion, its niceties and violations,

and their neighbors were part of it now,

who had come wishing to communicate —that big word

certain people use who have no gift for it.

The Imagined

If the imagined woman makes the real woman

seem bare-boned, hardly existent, lacking in

gracefulnesss and intellect and pulchritude,

and if you come to realize the imagined woman

can only satisfy your imagination, whereas

the real woman with all her limitations

can often make you feel good, how, in spite

of knowing this, does the imagined woman

keep getting into your bedroom, and joining you

at dinner, why is it that you always bring her along

on vacations when the real woman is shopping,

or figuring the best way to the museum?

And if the real woman

has an imagined man, as she must, someone

probably with her at this very moment, in fact

doing and saying everything she's ever wanted,

would you want to know that he slips in

to her life every day from a secret doorway

she's made for him, that he's present even when

you're eating your omelette at breakfast,

or do you prefer how she goes about the house

as she does, as if there were just the two of you?

Isn't her silence, finally, loving? And yours

not entirely self-serving? Hasn't the time come,

once again, not to talk about it?

seem bare-boned, hardly existent, lacking in

gracefulnesss and intellect and pulchritude,

and if you come to realize the imagined woman

can only satisfy your imagination, whereas

the real woman with all her limitations

can often make you feel good, how, in spite

of knowing this, does the imagined woman

keep getting into your bedroom, and joining you

at dinner, why is it that you always bring her along

on vacations when the real woman is shopping,

or figuring the best way to the museum?

And if the real woman

has an imagined man, as she must, someone

probably with her at this very moment, in fact

doing and saying everything she's ever wanted,

would you want to know that he slips in

to her life every day from a secret doorway

she's made for him, that he's present even when

you're eating your omelette at breakfast,

or do you prefer how she goes about the house

as she does, as if there were just the two of you?

Isn't her silence, finally, loving? And yours

not entirely self-serving? Hasn't the time come,

once again, not to talk about it?

Feathers

If a lone feather fell from the sky,

like a paper plane wafting down

from a tree house where a quiet boy

has been known to hide,

you might think message or perhaps

mischief, not just some mid-air

molting of a bird.

But what if many feathers fell

from a place seemingly higher

than any boy could ever climb,

beyond the top of Savage Mountain

and obscured by clouds,

what might you think then?

A flock of birds smithereened

by hunters? By a jet?

And let's say the feathers were large

and grayish, some of them bloody,

with signs of tendon and muscle

broken off, would you worry about

a resurgence of enormous raptors

only the Air Force knew about,

and had decided to destroy?

For years you've heard rumors

of homeless gods in the vast emptiness.

And if they would appear in your dreams,

as sometimes they did,

begging to be believed in once again,

you'd feel this icy refusal hardening in you.

And when you woke you'd feel it, too.

Your better self wished to believe

the feathers signaled a parade, an occasion

of a triumph, and what was falling

might be a new kind of confetti,

but what was there to celebrate?

Was the world, as you knew it, simply over,

no more rain or snow? Would there always be

just this strange detritus coming down,

covering what used to be the ground?

like a paper plane wafting down

from a tree house where a quiet boy

has been known to hide,

you might think message or perhaps

mischief, not just some mid-air

molting of a bird.

But what if many feathers fell

from a place seemingly higher

than any boy could ever climb,

beyond the top of Savage Mountain

and obscured by clouds,

what might you think then?

A flock of birds smithereened

by hunters? By a jet?

And let's say the feathers were large

and grayish, some of them bloody,

with signs of tendon and muscle

broken off, would you worry about

a resurgence of enormous raptors

only the Air Force knew about,

and had decided to destroy?

For years you've heard rumors

of homeless gods in the vast emptiness.

And if they would appear in your dreams,

as sometimes they did,

begging to be believed in once again,

you'd feel this icy refusal hardening in you.

And when you woke you'd feel it, too.

Your better self wished to believe

the feathers signaled a parade, an occasion

of a triumph, and what was falling

might be a new kind of confetti,

but what was there to celebrate?

Was the world, as you knew it, simply over,

no more rain or snow? Would there always be

just this strange detritus coming down,

covering what used to be the ground?

Bad

My wife is working in her room,

writing, and I've come in three times

with idle chatter, some no-new news.

The fourth time she identifies me

as what I am, a man lost

in late afternoon, in the terrible

in between - good work long over,

a good drink not yet

what the clock has okayed.

Her mood: a little bemused —

leave-me-the-hell-alone

mixed with a weary smile,

and I see my face

up on the Post Office wall

among Men Least Wanted,

looking forlorn. In the small print

under my name: Annoying

to loved ones in the afternoons,

lacks inner resources.

I go away, guilty as charged,

and write this poem, which I insist

she read at drinking time.

She's reading it now. It seems

she's pleased, but when she speaks

it's about charm, and how predictable

I am - how, when in trouble

I try to become irresistible

like one of those blond dogs

with a red bandanna around his neck,

sorry he's peed on the rug.

Forget it, she says, this stuff

is old, it won't work anymore,

and I hear Good boy, Good boy,

and can't stop licking her hand.

writing, and I've come in three times

with idle chatter, some no-new news.

The fourth time she identifies me

as what I am, a man lost

in late afternoon, in the terrible

in between - good work long over,

a good drink not yet

what the clock has okayed.

Her mood: a little bemused —

leave-me-the-hell-alone

mixed with a weary smile,

and I see my face

up on the Post Office wall

among Men Least Wanted,

looking forlorn. In the small print

under my name: Annoying

to loved ones in the afternoons,

lacks inner resources.

I go away, guilty as charged,

and write this poem, which I insist

she read at drinking time.

She's reading it now. It seems

she's pleased, but when she speaks

it's about charm, and how predictable

I am - how, when in trouble

I try to become irresistible

like one of those blond dogs

with a red bandanna around his neck,

sorry he's peed on the rug.

Forget it, she says, this stuff

is old, it won't work anymore,

and I hear Good boy, Good boy,

and can't stop licking her hand.

Don't Do That

It was bring-your-own if you wanted anything

hard, so I brought Johnnie Walker Red

along with some resentment I'd held in

for a few weeks, which was not helped

by the sight of little nameless things

pierced with toothpicks on the tables,

or by talk that promised to be nothing

if not small. But I'd consented to come,

and I knew in what part of the house

their animals would be sequestered,

whose company I loved. What else can I say,

except that old retainer of slights and wrongs,

that bad boy I hadn't quite outgrown —

I'd brought him along too. I was out

to cultivate a mood. My hosts greeted me,

but did not ask about my soul, which was when

I was invited by Johnnie Walker Red

to find the right kind of glass, and pour.

I toasted the air. I said hello to the wall,

then walked past a group of women

dressed to be seen, undressing them

one by one, and went up the stairs to where

the Rottweilers were, Rosie and Tom,

and got down with them on all fours.

They licked the face I offered them,

and I proceeded to slick back my hair

with their saliva, and before long

I felt like a wild thing, ready to mess up

the party, scarf the hors d'oeuveres.

But the dogs said, No, don't do that,

calm down, after a while they open the door

and let you out, they pet your head, and everything

you might have held against them is gone,

and you're good friends again. Stay, they said.

hard, so I brought Johnnie Walker Red

along with some resentment I'd held in

for a few weeks, which was not helped

by the sight of little nameless things

pierced with toothpicks on the tables,

or by talk that promised to be nothing

if not small. But I'd consented to come,

and I knew in what part of the house

their animals would be sequestered,

whose company I loved. What else can I say,

except that old retainer of slights and wrongs,

that bad boy I hadn't quite outgrown —

I'd brought him along too. I was out

to cultivate a mood. My hosts greeted me,

but did not ask about my soul, which was when

I was invited by Johnnie Walker Red

to find the right kind of glass, and pour.

I toasted the air. I said hello to the wall,

then walked past a group of women

dressed to be seen, undressing them

one by one, and went up the stairs to where

the Rottweilers were, Rosie and Tom,

and got down with them on all fours.

They licked the face I offered them,

and I proceeded to slick back my hair

with their saliva, and before long

I felt like a wild thing, ready to mess up

the party, scarf the hors d'oeuveres.

But the dogs said, No, don't do that,

calm down, after a while they open the door

and let you out, they pet your head, and everything

you might have held against them is gone,

and you're good friends again. Stay, they said.